Etiology and prevention of prevalent types of cancer

Ercole L. Cavalieri1,2* and Eleanor G. Rogan1,2

1Eppley Institute for Research in Cancer and Allied Diseases, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-6805, USA

2Department of Environmental, Agricultural and Occupational Health, College of Public Health, University of Nebraska Medical Center, Omaha, NE 68198-4388, USA

Abstract

Endogenous estrogens become carcinogens when excessive catechol estrogen quinone metabolites are formed. Specifically, the catechol estrogen-3,4-quinones can react with DNA to produce a large amount of specific depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts, formed at the N-3 of Ade and N-7 of Gua. Loss of these adducts leaves apurinic sites in the DNA, which can generate subsequent cancer-initiating mutations. Unbalanced estrogen metabolism yields excessive catechol estrogen-3,4-quinones, increasing formation of the depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts and the risk of initiating cancer. Evidence for this mechanism of cancer initiation comes from studies in vitro, in cell culture, in animal models and in human subjects. High levels of estrogen-DNA adducts have been observed in women with breast, ovarian or thyroid cancer, and in men with prostate cancer or non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Observation of high levels of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts in high risk women before the presence of breast cancer indicates that adduct formation is a critical factor in breast cancer initiation. Two dietary supplements, N-acetylcysteine and resveratrol, complement each other in reducing formation of catechol estrogen-3,4-quinones and inhibiting formation of estrogen-DNA adducts in cultured human and mouse breast epithelial cells. They also inhibit malignant transformation of these epithelial cells. In addition, formation of adducts was reduced in women who followed a Healthy Breast Protocol that includes N-acetylcysteine and resveratrol. Blocking initiation of cancer prevents promotion, progression and development of the disease. These results suggest that reducing formation of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts can reduce the risk of developing a variety of types of human cancer.

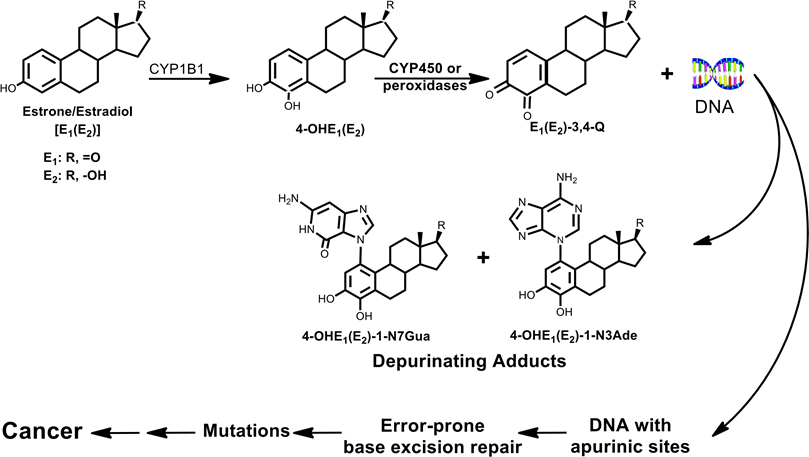

Cancer is often a problem of chemical carcinogenesis. This means that chemicals are frequently involved in the process leading to cancer. The chemicals that cause much of human cancer are the estrogens, which can form excessive carcinogenic catechol estrogen-3,4-quinone metabolites (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Major metabolic pathway (97%) in cancer initiation by estrogens

Estrogen metabolism leading to the formation of estrogen-DNA adducts

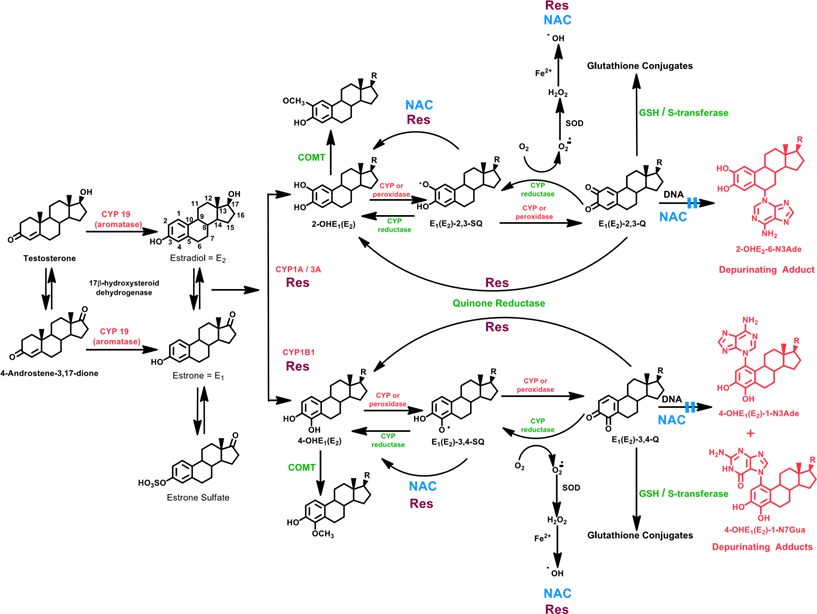

Estrogens are metabolized via two major pathways: formation of 16α-hydroxyestrone (estradiol) [E1(E2)] (not shown in Figure 2) and formation of the catechol estrogens 2-OHE1(E2) and 4-OHE1(E2)1. Cytochrome P450 (CYP) 1A1 hydroxylates E1 and E2 preferentially at the 2-position, whereas CYP1B1 hydroxylates almost exclusively at the 4-position2-4, and the 4-OHE1(E2) are the most important metabolites in cancer initiation (Figure 1)5-7. The most common pathway of conjugation of catechol estrogens in extrahepatic tissues is O-methylation, catalyzed by catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT)8,9. When COMT activity is low, competitive oxidation of catechol estrogens to semiquinones and then to quinones, catalyzed by CYP or peroxidases, can occur (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Formation of estrogens, catechol estrogen metabolic pathway of estrogens and depurinating DNA adducts of estrogens. Activating enzymes and depurinating DNA adducts are in red, and protective enzymes are in green. N-Acetylcysteine (NAC, shown in blue) and resveratrol (Res, shown in burgundy) indicate various steps where NAC and Res can ameliorate unbalanced estrogen metabolism and reduce formation of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts.

Following formation of catechol estrogen quinones, they can be inactivated by reaction with glutathione (GSH) or reduction to their catechols by quinone reductase (NQO1)10,11, a protective enzyme induced by various compounds12. If the catechol estrogen quinones are not eliminated by protective processes, they can react with DNA (Figure 2). Catechol estrogen quinones covalently bind to DNA to form two types of adducts: stable ones that remain in DNA unless removed by repair and depurinating adducts that are lost from DNA by destabilization of the glycosyl bond13,14.

Apurinic sites and mutations

Evidence that depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts play a critical role in cancer initiation comes from a correlation between depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts that generate apurinic sites and oncogenic Harvey (H)-ras mutations in preneoplastic mouse skin15 and rat mammary gland16. Apurinic sites occur spontaneously in cells17. In mouse skin treated with E2-3,4-quinone (Q), however, the number of apurinic sites is 145 times greater than the number of spontaneously formed sites15,18, presumably overwhelming the repair mechanism and generating mutations.

Estrogens have been thought to be epigenetic carcinogens that stimulate abnormal cell proliferation through estrogen receptor (ER)-mediated processes19-21. This stimulated cell proliferation could lead to increased genetic damage and initiate cancer20-22. We do not consider ER-mediated processes to be significantly involved in cancer initiation for a variety of reasons. First, 4-OHE1(E2) have higher carcinogenic potency than 2-OHE1(E2)5-7, which cannot be explained by ER-mediated processes. Second, ERKO/Wnt-1 mice, which have no functional ER-α, develop estrogen-induced mammary tumors23-25.

When mouse skin treated with E2-3,4-Q was analyzed for both formation of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts and H-ras mutations, predominantly the depurinating 4-OHE1(E2)-1-N3Ade and 4-OHE1(E2)-1-N7Gua adducts were formed (>99%) and mostly A to G mutations were detected only 6-12 h after treatment15. Similar results were obtained when rat mammary gland was treated with E2-3,4-Q16.

Estrogen mutagenicity has also been demonstrated in transfected Big Blue® rat2 embyronic cells26 and Big Blue® rats treated with 4-OHE218. The generation of mutations in mouse skin, rat mammary gland and cultured cells shows that estrogens are, indeed, directly mutagenic.

Cancer initiation

Imbalanced estrogen metabolism can lead to excessive production of catechol estrogen-3,4-quinones that generate estrogen-DNA adducts. These imbalances can lead to excessive formation of estrogens because of overexpression of CYP19 (aromatase)27-29 and unregulated sulfatase that converts stored E1-sulfate into E130,31. If CYP1B1 is overexpressed, higher levels of 4-OHE1(E2) will be available2-4 for conversion into E1(E2)-3,4-Q, the strongest carcinogenic metabolites of estrogens (Figure 1). Polymorphic variations in COMT can limit the activity of this enzyme, allowing more 4-OHE1(E2) to be converted into E1(E2)-3,4-Q9,32. Polymorphisms in NQO1 can lead to decreased reduction of the catechol estrogen quinones back to catechol estrogens33, again leaving more quinones available to react with DNA, unless they are removed by reaction with GSH.

Imbalances in estrogen metabolism have been observed in several animal models for estrogen carcinogenicity: the kidney of male Syrian golden hamsters34, prostate of Noble rats35 and mammary gland of transgenic estrogen receptor-α knock-out mice24. These imbalances have also been observed in breast tissue of women with breast cancer. In tumor-adjacent breast tissue, the levels of 4-OHE1(E2) were almost four-times higher than those in breast tissue from women without breast cancer36. The breast tissue from women with breast cancer also demonstrated greater expression of the estrogen-activating enzymes CYP19 and CYP1B1, compared to women without breast cancer, who exhibited greater expression of the estrogen-protective enzymes COMT and NQO137.

The ability of estrogens to induce malignant transformation of mammalian cells has been demonstrated in cultured human and mouse mammary epithelial cells. When the human non-transformed MCF-10F cells were treated with E2, depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts were formed and the cells were malignantly transformed in a dose-dependent manner38. Similarly, when non-transformed mouse E6 cells were treated with 4-OHE2 or E2-3,4-Q, the cells formed depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts and were malignantly transformed in a dose-dependent manner39. Such studies demonstrate a critical role of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts in the processes leading to malignant transformation.

Depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts: biomarkers of cancer risk and initiation

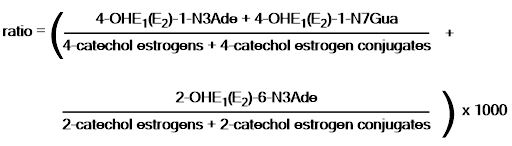

The first evidence that depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts play a major role in cancer initiation was obtained from a correlation between the sites of formation of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts and H-ras mutations in mouse skin and rat mammary gland treated with the ultimate carcinogenic metabolite E2-3,4-Q15,16. Estrogen metabolites, estrogen-GSH conjugates and depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts can now be analyzed in human serum and urine by using ultraperformance liquid chromatography/tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS). The ratio of the depurinating adducts, 4-OHE1(E2)-1-N3Ade, 4-OHE1(E2)-1-N7Gua and 2-OHE1(E2)-6-N3Ade, to estrogen metabolites and conjugates provides a reliable measure of the balance or imbalance of estrogen metabolism in a person:

This ratio serves as a biomarker for risk of developing estrogen-initiated cancer40,41.

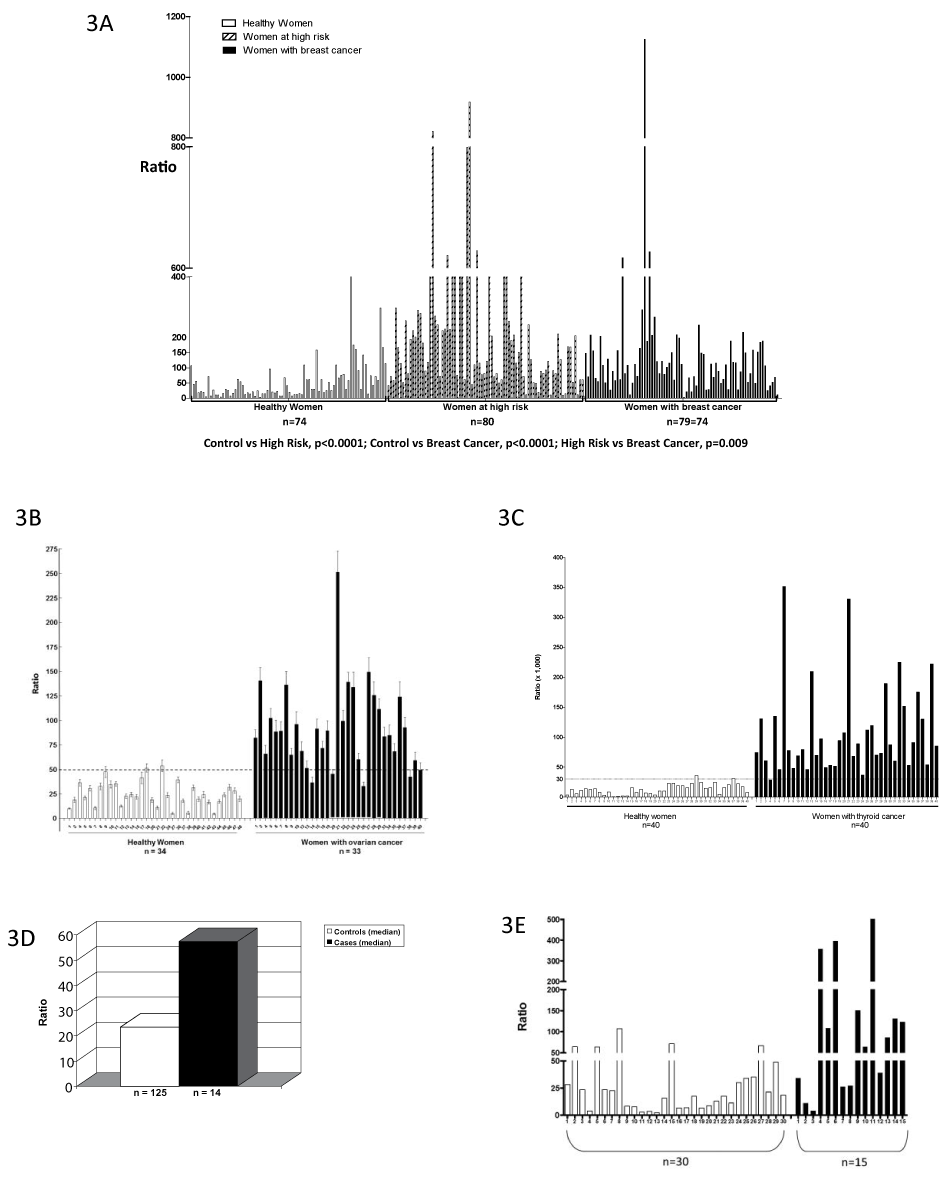

Caucasian women diagnosed with breast cancer, or at normal or high risk for developing the disease, have been investigated in three case-control studies40,42,43. In the first two, a spot urine sample was analyzed by UPLC-MS/MS and the estrogen-DNA adduct ratio (see above) was calculated for each subject40,42. The ratios in the high-risk women and those diagnosed with breast cancer were significantly higher than those in the normal-risk women (p<0.001 in both studies)40,42. The third study used serum samples, and similar results were obtained, with even greater differences between the normal-risk women and high-risk women or those with breast cancer [p<0.0001, Figure 3(a)]43. No differences in the results were observed when the subjects were separated into pre- and peri/postmenopausal groups43. These results, especially the high ratios observed in high-risk women, indicate that formation of estrogen-DNA adducts plays a critical role in the etiology of breast cancer.

The ratio of estrogen-DNA adducts to metabolites and conjugates was also investigated in women with and without ovarian cancer44. The women diagnosed with ovarian cancer demonstrated higher ratios than the controls [p<0.0001, Figure 3(b)]. DNA from saliva samples was purified and single nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) were analyzed in the genes for the estrogen-activating enzyme CYP1B1 (V432L) and the protective enzyme COMT (V158M)44. The women with two copies of both the low-activity COMT allele plus the high-activity CYP1B1 allele demonstrated much higher values of the DNA adduct ratio, and the odds ratio for ovarian cancer was 6-fold higher compared to women with the normal-activity alleles of the enzymes. These combined results suggest that initiation of ovarian cancer is strongly associated with unbalanced estrogen metabolism leading to formation of estrogen-DNA adducts.

When estrogen metabolites, conjugates and depurinating DNA adducts were analyzed in a small study of urine samples from women with and without thyroid cancer, the women with thyroid cancer had much higher ratios of estrogen-DNA adducts to estrogen metabolites and conjugates [p<0.0001, Figure 3(c)]45.

Formation of estrogen-DNA adducts has also been associated with cancer in men46-48, and the same adduct ratio can be used as a biomarker of risk. Urine samples from men with and without prostate cancer have been analyzed by UPLC-MS/MS46,47. In an initial study, diagnosis with prostate cancer was associated with significantly higher levels of the depurinating adduct 4-OHE1(E2)-1-N3Ade46. In a subsequent, larger study, the estrogen-DNA adduct ratio was significantly higher in men with prostate cancer than in controls [p<0.001, Figure 3(d)]47. These results suggest that formation of estrogen-DNA adducts plays a critical role in the etiology of prostate cancer.

In a similar small study of men diagnosed with non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) plus healthy controls, the adduct ratio was significantly higher in men with NHL compared to controls [p<0.0007, Figure 3(e)]48. We think that investigation of other prevalent types of cancer will demonstrate that they, too, are initiated by formation of estrogen-DNA adducts. These cancers include brain, colon, endometrium, kidney, leukemia, lung of non-smokers, melanoma, myeloma, pancreas and testis.

Figure 3. Ratios of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts to estrogen metabolites and estrogen conjugates in (a) serum samples from healthy women, high-risk women and women with breast cancer43; (b) urine samples from women with and without ovarian cancer (p<0.0001)44; (c) urine samples from women with and without thyroid cancer (p<0.0001). The dotted line at a ratio of 50 is the cut-point for sensitivity and specificity of the ratio45; (d) urine samples from men with and without prostate cancer (mean levels, p<0.001)47; and (e) urine samples from men with and without NHL (p<0.007)48.

In summary, the ratio of estrogen-DNA adducts to estrogen metabolites and conjugates was significantly higher in cases compared to controls in all five types of cancer studied: breast, ovarian, thyroid and prostate cancers, plus NHL. The high adduct ratios in women at high risk for breast cancer and the association of SNPs in CYP1B1 and COMT with increased odds of ovarian cancer provide particularly strong evidence for a critical role of estrogen-DNA adducts in the etiology of these cancers.

By using sensitivity and specificity curves for the ratio levels, an initial cut-point of 77 for breast cancer43, 43 for ovarian cancer44 and 30 for thyroid cancer45 was determined. This suggests that DNA adduct ratios above 77 indicate high risk for cancer, while ratios below 30 indicate low risk, while ratios of 30-77 are indeterminate. Additional studies with more subjects and other types of cancer will enable refinement of this potential biomarker of cancer risk.

Prevention of cancer

When estrogen metabolism is unbalanced, the level of catechol estrogen quinones increases and then more depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts are formed. This can be inhibited by balancing estrogen metabolism through the use of specific dietary supplements such as N-acetylcysteine (NAC) and resveratrol (Res). These two compounds are particularly effective in preventing the formation of estrogen-DNA adducts because they inhibit formation of catechol estrogen quinones and/or their reaction with DNA49.

NAC has very low toxicity, but has multiple anticarcinogenic properties50,51 and can generate the cellular scavenger GSH. NAC reacts efficiently with the electrophilic E1(E2)-3,4-Q49, preventing them from forming adducts with DNA. By reducing catechol estrogen semiquinones to catechol estrogens (Figure 2)52 and/or reacting with E1(E2)-3,4-Q, NAC prevents malignant transformation of human MCF-10F cells53 and mouse E6 mammary cells39 treated with 4-OHE2.

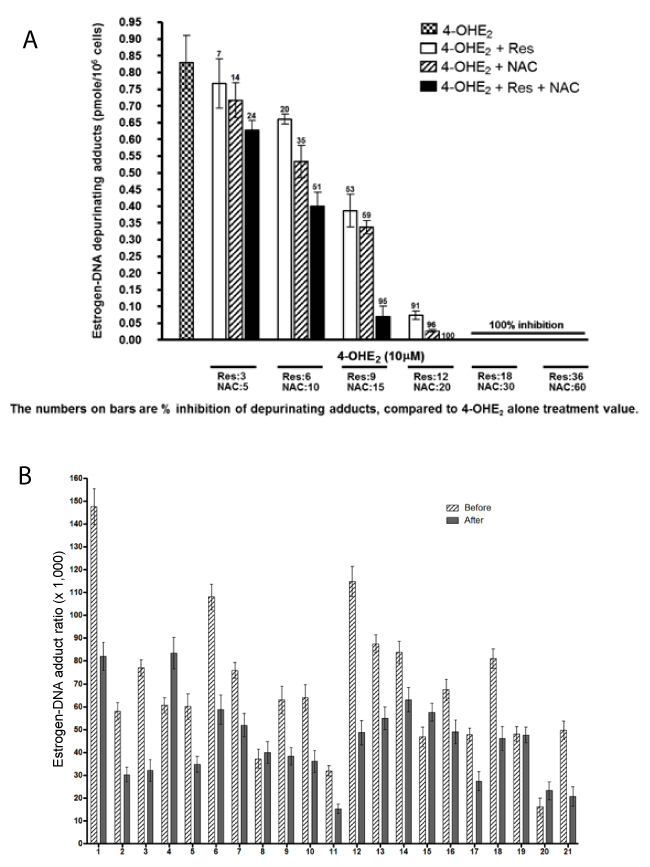

Both NAC and Res can cross the blood-brain barrier50,51,54,55. Res has chemopreventive effects54,55, can modulate CYP1B138,56, induce quinone reductase38,57 and reduce catechol estrogen semiquinones to catechol estrogens38. Res inhibits formation of estrogen-DNA adducts in MCF-10F cells treated with 4-OHE238,58. When MCF-10F cells were treated with 4-OHE2 and NAC, Res or NAC plus Res, the compounds inhibited formation of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts in an additive manner [p<0.0001, Figure 4(a)]59.

The effects of NAC and Res were studied as part of a Healthy Breast Protocol for women60. Healthy women, never diagnosed with cancer, followed the Healthy Breast Protocol daily for three months and provided a spot urine sample immediately before and after the treatment. The urine samples were analyzed for estrogen metabolites, estrogen conjugates and depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts by using UPLC-MS/MS, and the adduct ratio was calculated for each sample [Figure 4(b)]. Among the 21 participants, 16 showed lower adduct ratios after treatment, four showed no change and one had a higher ratio. The average decrease in adduct ratio after treatment with the Healthy Breast Protocol was statistically significant (p<0.03)60. These results indicate that a treatment protocol with NAC and Res can reduce formation of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts in people.

Figure 4. (a) Effects of NAC, Res, or NAC plus Res on the formation of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts in MCF-10F cells treated with 4-OHE2. The number above each bar indicates the percent inhibition compared to treatment with only 4-OHE259. (b) Estrogen-DNA adduct ratios in women before and after following the Healthy Breast Protocol for three months60.

In summary, NAC and Res have a variety of effects that can play a role in reducing formation of estrogen-DNA adducts, thus reducing the risk of developing cancer.

Conclusions

Imbalanced estrogen metabolism can lead to excessive formation of carcinogenic catechol estrogen-3,4-quinones. Reaction of these quinones with DNA predominantly leads to depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts that can generate mutations to initiate many prevalent types of human cancer. These adducts can serve as biomarkers for risk of developing cancer.

Since formation of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts is a critical event in cancer initiation, reducing their formation can reduce the risk of developing cancer. N-acetylcysteine and resveratrol impede formation of these adducts through complementary mechanisms, suggesting a widely applicable approach to cancer prevention. Since preventing cancer-leading mutations would stop the development of cancer, it is not necessary to know which mutations lead to which types of cancer. This is one of the reasons why preventing formation of estrogen-DNA adducts can be such a powerful cancer prevention tool.

Acknowledgements

Core support at the Eppley Institute was supported by grant P30 36727 from the National Cancer Institute.

References

- Zhu BT, Conney AH. Functional role of estrogen metabolism in target cells: review and perspectives. Carcinogenesis. 1998; 9: 1-27.

- Spink DC, Hayes CL, Young NR, et al. The effects of 2,3,7,8-tetrachlorodibenzo-p-dioxin on estrogen metabolism in mcf-7 breast cancer cells: Evidence for induction of a novel 17 beta-estradiol 4-hydroxylase. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 1994; 51: 251-8.

- Hayes CL, Spink DC, Spink BC, et al. 17β-estradiol hydroxylation catalyzed by human cytochrome p450 1b1. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1996; 93: 9776-81.

- Spink DC, Spink BC, Cao JQ, et al. Differential expression of CYP1a1 and CYP1b1 in human breast epithelial cells and breast tumor cells. Carcinogenesis. 1998;19: 291-8.

- Liehr JG, Fang WF, Sirbasku DA, et al. Carcinogenicity of catechol estrogens in Syrian hamsters. J Steroid Biochem. 1986; 24: 353-6.

- Li JJ, Li SA. Estrogen carcinogenesis in Syrian hamster tissues: role of metabolism. Fed Proc. 1987; 46: 1858-63.

- Newbold RR, Liehr JG. Induction of uterine adenocarcinoma in CD-1 mice by catechol estrogens. Cancer Res. 2000; 60: 235-7.

- Männistö PT, Kaakkola S. Catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT): Biochemistry molecular biology pharmacology and clinical efficacy of the new selective COMT inhibitors. Pharmacol Rev. 1999; 51: 593-628.

- Yager J. Catechol-O-methyltransferase: characteristics, polymorphisms and role in breast cancer. Drug Discov Today Dis Mech. 2013; 9: e41-6.

- Gaikwad NW, Rogan EG, Cavalieri EL. Evidence from ESI-MS for NQO1-catalyzed reduction of estrogen ortho-quinones. Free Radic Biol Med. 2007; 43(9): 1289-98.

- Gaikwad NW, Yang L, Rogan EG, et al. Evidence for NQO2-mediated reduction of the carcinogenic estrogen ortho-quinones. Free Radic Biol Med. 2009; 46: 253-62.

- Talalay P, Dinkova Kostova AT, Holtzclaw WD. Importance of phase 2 gene regulation in protection against electrophile and reactive oxygen toxicity and carcinogenesis. Adv Enzyme Regul. 2003; 43: 121-34.

- Stack DE, Byun J, Gross ML, et al. Molecular characteristics of catechol estrogen quinones in reactions with deoxyribonucleosides. Chem Res Toxicol. 1996; 9: 851-9.

- Li KM, Todorovic R, Devanesan P, et al. Metabolism and DNA binding studies of 4-hydroxyestradiol and estradiol-3,4-quinone in vitro and in female ACI rat mammary gland in vivo. Carcinogenesis. 2004; 25: 289-97.

- Chakravarti D, Mailander P, Li KM, et al. Evidence that a burst of DNA depurination in SENCAR mouse skin induces error-prone repair and forms mutations in the H-ras gene. Oncogene. 2001; 20: 7945-53.

- Mailander PC, Meza JL, Higginbotham S, et al. Induction of A.T to G.C mutations by erroneous repair of depurinated DNA following estrogen treatment of the mammary gland of ACI rats. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2006; 101: 204-15.

- Lindahl T, Nyberg B. Rate of depurination of native deoxyribonucleic acid. Biochemistry. 1972; 11: 3610-8.

- Cavalieri E, Chakravarti D, Guttenplan J, et al. Catechol estrogen quinones as initiators of breast and other human cancers. Implications for biomarkers of susceptibility and cancer prevention. BBA-Reviews on Cancer. 2006; 1766: 63-78.

- Li JJ, Li A. Estrogen carcinogenesis in hamster tissues: A critical review. Endocr Rev. 1990; 11: 534-31.

- Feigelson HS, Henderson BE. Estrogens and breast cancer. Carcinogenesis. 1996; 17: 2279-84.

- Nandi S, Guzman RC, Yang J. Hormones and mammary carcinogenesis in mice, rats and humans: a unifying hypothesis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1995; 92: 3650-7.

- Hahn WC, Weinberg RC. Rules for making tumor cells. N Engl J Med. 2002; 347: 1593-1603.

- Bocchinfuso WP, Hively WP, Couse JF, et al. A mouse mammary tumor virus-Wnt-1 transgene induces mammary gland hyperplasia and tumorigenesis in mice lacking estrogen receptor-α. Cancer Res. 1999; 59: 1869-76.

- Devanesan P, Santen RJ, Bocchinfuso WP, et al. Catechol estrogen metabolites and conjugates in mammary tumors and hyperplastic tissue from estrogen receptor alpha knock out (ERKO)/Wnt 1 mice; implications for initiation of mammary tumors. Carcinogenesis. 2001; 22: 1573-6.

- Santen R, Cavalieri E, Rogan E, et al. Estrogen mediation of breast tumor formation involves estrogen receptor-dependent, as well as independent, genotoxic effects. Ann NY Acad Sci. 2006; 1155: 132-40.

- Zhao Z, Kosinska W, Khmelnitsky M, et al. Mutagenic activity of 4-hydroxyestradiol but not 2-hydroxyestradiol in BB2 rat embryonic cells and the mutational spectrum of 4-hydroxyestradiol. Chem Res Toxicol. 2006; 19: 475-9.

- Miller WR, O’Neill J. The importance of local synthesis of estrogen within the breast. Steroids. 1987; 50: 537-48.

- Simpson ER, Mahendroo MS, Means GD, et al. Aromatase cytochrome P450, the enzyme responsible for estrogen biosynthesis. Endocr Rev. 1994; 15: 342-55.

- Jefcoate CR, Liehr JG, Santen RJ, et al. Tissue-specific synthesis and oxidative metabolism of estrogens. In: Cavalieri E, Rogan E, editors. JNCI Monograph 27: Estrogens as Endogenous Carcinogens in the Breast and Prostate. Oxford University Press. 2000; p. 95-112.

- Santner SJ, Feil PD, Santen RJ. In situ estrogen production via the estrone sulfatase pathway in breast tumors: Relative importance versus the aromatase pathway. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1984; 59: 29-33.

- Pasqualini JR, Chetrite G, Blacker D, et al. Concentrations of estrone, estradiol, and estrone sulfate and evaluation of sulfatase and aromatase activities in pre- and postmenopausal breast cancer patients. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 1996; 81: 1460-4.

- Mitrunen K, Hirvonen A. Molecular epidemiology of sporadic breast cancer. The role of polymorphic genes involved in oestrogen biosynthesis and metabolism. Mutat Res. 2003; 544: 9-41.

- Singh S, Zahid M, Saeed M, et al. NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 Arg139Trp and Pro187Ser polymorphism imbalance estrogen metabolism towards DNA adduct formation in human mammary epithelial cells. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009; 117: 56-66.

- Cavalieri EL, Kumar S, Todorovic R, et al. Imbalance of estrogen homeostasis in kidney and liver of hamsters treated with estradiol: implications for estrogen-induced initiation of renal tumors. Chem Res Toxicol. 2001; 14: 1041-50.

- Cavalieri EL, Devanesan P, Bosland MC, et al. Catechol estrogen metabolites and conjugates in different regions of the prostate of Noble rats treated with 4-hydroxyestradiol: implications for estrogen-induced initiation of prostate cancer, Carcinogenesis. 2002; 23: 329-33.

- Rogan EG, Badawi AF, Devanesan PD, et al. Relative imbalances in estrogen metabolism and conjugation in breast tissue of women with carcinoma: potential biomarkers of susceptibility to cancer. Carcinogenesis 2003; 24: 697-702.

- Singh S, Chakravarti D, Edney JA, et al. Relative imbalances in the expression of estrogen-metabolizing enzymes in the breast tissue of women with breast carcinoma. Oncol Rep. 2005; 14: 1091-6.

- Lu F, Zahid M, Wang C, et al. Resveratrol prevents estrogen-DNA adduct formation and neoplastic transformation in MCF-10F cells. Cancer Prev Res. 2008; 1: 135-45.

- Venugopal D, Zahid M, Mailander PC, et al. Reduction of estrogen-induced transformation of mouse mammary epithelial cell by N-acetylcysteine. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008; 109: 22-30.

- Gaikwad NW, Yang L, Muti P, et al. The molecular etiology of breast cancer: evidence from biomarkers of risk. Int J Cancer. 2008; 122: 1949-57.

- Cavalieri EL, Rogan EG. Inhibition of depurinating estrogen-DNA adduct formation in the prevention of breast and other cancers. In: Russo, J., ed. Trends in Breast Cancer Prevention Chapter 6 Springer Switzerland. 2016; pp. 113-145.

- Gaikwad NW, Yang L, Pruthi S, et al. Urine biomarkers of risk in the molecular etiology of breast cancer. Breast Cancer: Basic & Clinical Research. 2009; 3: 1-8.

- Pruthi S, Yang L, Sandhu NP, et al. Evaluation of serum estrogen-DNA adducts as potential biomarkers breast cancer risk. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2012; 132: 73-9.

- Zahid M, Beseler CL, Hall JB, et al. Unbalanced estrogen metabolism in ovarian cancer. Int J Cancer. 2014; 134: 2414-23.

- Zahid M, Goldner W, Beseler CL, et al. Unbalanced estrogen metabolism in thyroid cancer. Int J Cancer. 2013; 133: 2642-9.

- Markushin Y, Gaikwad N, Zhang H, et al. Potential biomarker for early risk assessment of prostate cancer. Prostate. 2006; 66: 1565-71.

- Yang L, Gaikwad N, Meza J, et al. Novel biomarkers for risk of prostate cancer. Results from a case-control study. Prostate. 2009; 69: 41-8.

- Gaikwad NW, Yang L, Weisenburger DD, et al. Urinary biomarkers suggest that estrogen-DNA adducts may play a role in the aetiology of non-Hodgkin lymphoma. Biomarkers. 2009; 14: 502-12.

- Zahid M, Gaikwad N, Rogan EG, et al. Inhibition of depurinating estrogen-DNA adducts formation by natural compounds. Chem Res Toxicol. 2007; 20: 1947-53.

- De Flora S. et al. Mechanisms of anticarcinogenesis: The example of N-acetylcysteine. In: Ioannides C, Lewis DFV, editors. Drugs, Diet and Disease. Mechanistic Approaches to Cancer Herts, UK Prentice Hall 1994; p 151-202.

- De Flora S, Cesarone CF, Balansky RM, et al. Chemopreventive properties and mechanisms of N-acetylcysteine. The experimental background. J Cell Biochem Suppl. 1995; 22: 33-41.

- Samuni AM, Chuang EY, Krishna MC, et al. Semiquinone radical intermediate in catecholic estrogen-mediated cytotoxicity and mutagenesis: chemoprevention strategies with antioxidants. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2003; 100: 5390-5.

- Zahid M, Saeed M, Ali MF, et al. N-acetylcysteine blocks formation of cancer-initiating estrogen-DNA adducts in cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2010; 49: 392-400.

- Jang M, Cai L, Udeani GO, et al. Cancer chemopreventive activity of resveratrol, a natural product derived from grapes. Science. 1997; 275: 218-20.

- Aziz MH, Kumar R, Ahmad N. Cancer chemoprevention by resveratrol: in vitro and in vivo studies and the underlying mechanisms (review). Int J Oncol. 2003; 23: 17-28.

- Guengerich FP, Chunb YJ, Kima D, et al. Cytochrome P450 1B1: a target for inhibition in anticarcinogenesis strategies. Mutat Res. 2003; 523-524: 173-82.

- Floreani M, Napoli E, Quintieri L, et al. Oral administration of trans-resveratrol to guinea pigs increases cardiac DT-diaphorase and catalase activities, and protects isolated atria from menadione toxicity. Life Sci. 2003; 7224: 2741-50.

- Zahid M, Gaikwad NW, Ali MF, et al. Prevention of estrogen-DNA adducts in MCF-10F cells by resveratrol. Free Radic Biol Med. 2008; 45: 136-45.

- Zahid M, Saeed M, Beseler C, et al. Resveratrol and N-acetylcysteine block the cancer-initiating step in MCF-10F cells. Free Radic Biol Med. 2011; 50: 78-85.

- Muran P, Muran S, Beseler CL, et al. Breast health and reducing breast cancer risk, a functional medicine approach. J Altern Complement Med. 2015; 21: 321-6.